The seventh installment of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House is comprised of the 20th, 21st, and 22nd chapters. Not only does the seventh installment not include Esther Summerson’s narrative, which readers may have grown accustomed to, but there is no appearance of the character at all within the three chapters. The chapters of the September 1852 installment, instead, are titled “A New Lodger” (314), “The Smallweed Family” (332), and “Mr. Bucket” (352). Each chapter introduces a new character, or group of characters to the plot through the lens of the familiar omniscient narrator. Chapter 20 introduces readers to Tony Jobling, a friend of Guppy’s who fills Nemo’s old room, and agrees to spy on Krook. Chapter 21 repositions readers with a view of the always “old” Smallweed family, who is visited by a friendly trooper, George, stopping to repay debts. At the end of this chapter the omniscient narrator follows George to his own shooting gallery, where we meet the scarred man who lives in the plain building with him, Phil Squod. The installment concludes with the 22nd chapter, in which Mr. Bucket, a detective enlisted by Tulkinghorn, is introduced. He investigates the mysterious woman who had inquired to Jo about Nemo’s death. Mr. Snagsby and Mr. Bucket venture to Tom-All-Alone’s where they encounter life in a poor neighborhood and find Jo. By the end of the chapter, it is revealed that Madamoiselle Hortense is no longer considered the suspect, and the question of the mystery woman’s identity remains unanswered.

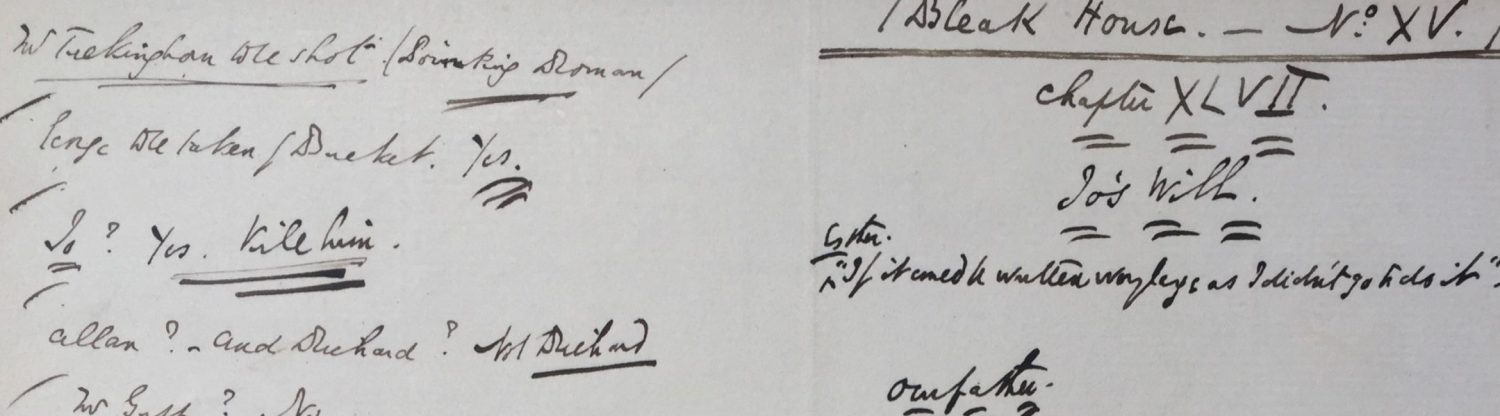

Despite the readjustment in focus from many existing characters, the chapters of this installment are imperative to Bleak House. Through new character formulations, installment seven provides functional links between the characters and settings already established before the September issue, and the monthly installments that follow. This installment also highlights certain events and interactions to underscore the overarching purpose of social satire that extends from the beginning of Bleak House to the final installment. These functions are supported by Dickens’s working notes, wherein some of these essential characteristics and important interactions are emphasized by additional ink markings.

In Chapter 20, the omniscient narrator follows Mr. Guppy in order to produce a new character: Tony Jobling. Jobling, who by the end of the chapter operates under the alias Mr. Weevle, functions to encourage readers to become acquainted with the new character and his relationship to Mr. Guppy, the law, and Krook. The organization of the relationship between these three men is explicitly mapped the in chapter “A New Lodger” in order to construct a dynamic that becomes more significant twelve chapters later, in “The Appointed Time”, when Krook is discovered to have spontaneously combusted. Beyond this functional purpose of Jobling, his lack of stable identity may hold a more allegorical purpose. The chapter’s title is dedicated to Jobling, but uses neither his original name nor his assumed name. Rather, the character is reduced to his occupation of a room in the chapter title “A New Lodger”. This sets chapter 20 apart from the following two chapters in the installment, which directly cite the focal characters’ names. The erasure of Jobling’s name from the title and the alias assigned to him by Guppy may serve to contribute to the satirical tone of Bleak House, by indirectly blaming this fluidity on the character’s relationship with the law. Guppy’s ascription of “Weevle” to Jobling for Guppy’s own interests about Krook’s involvement with legal papers shows his methodical process. “Weevle” is just another general, fictitious name like Coodle, Doodle, Boodle, Duffy, and Cuffy (Dickens 190). This signifies how people so consumed with the law, or in Jobling’s case, people used as devices by others who are completely fixated in legal matters, can be reduced, manipulated, and completely warped into different characters by the association.

The middle portion of Bleak House’s seventh installment launches a new character grouping: The Smallweed family. The main characterization of the family as a whole is the incredible age each character exhibits; even the twin teenage grandchildren are continually represented as remarkably old. This chapter is largely focused on social critique by magnifying the family’s concern with money, whether that be through sore feelings on the subject or greedy prospects, and the unnatural age that accompanies this capital focus.

“There has been only one child in the Smallweed family for several generations. Little old men and women there have been, but no child, until Mr. Smallweed’s grandmother, now living, became weak in her intellect and fell (for the first time) into a childish state.” (332)

The necessity and thirst for money can become an all-encompassing matter which robs people of youth by acceleration into working-class adulthood. Charley’s appearance in the chapter is interesting, and adds yet another layer to social commentary when the Smallweed family exploits the work of poor Charley.

“Timidly obedient to the summons, a little girl in a rough apron and a large bonnet, with her hands covered with soap and water and a scrubbing brush in one of them, appears, and curtseys.” (336)

Even Charley, an outsider of the family, is accelerated into responsible maturity far beyond her physical maturity, for the dire necessity of money. Judy’s callous treatment towards the young girl generates even more tension for readers.

Chapter 21 in the seventh installment also functions by extending Bleak House’s setting. The trooper, George, is the vehicle through which the omniscient narrator travels from the Smallweeds’ residence to George’s Shooting Gallery, &c. This establishes the shooting gallery as a casual, mostly blank-canvas setting with potential; this comes to significance in installment 15, with the discovery of Tulkinghorn’s body, followed by George’s arrest.

Chapter 22, “Mr. Bucket”, is arguably the most important chapter in the seventh installment, with the introduction of detective Mr. Bucket. This character reappears in later installments to drive much of the plot to its finale. The inclusion of Mr. Bucket at this point in the installments, just before the mid-point, seems to be a strategic decision about reader engagement for the serial format. After six months of continual question materialization and very few answers, the introduction of Bucket presents readers with a character whose purpose is to collect information and answer questions. The name “Mr. Bucket” itself embodies the investigative man who constantly collects puzzle pieces of information, and although it takes more time for the omniscient narrator to notify readers of Bucket’s discoveries, the existence of the character alone seems to imply an eventual pay-off for invested readers. This chapter also functions to stall and moderate pace; Jo identifies evidence, but Mademoiselle Hortense is the wrong body filling “the wale, the bonnet, and the gownd” (364). The mystery of the inquisitive woman is prolonged, and the last chapter for the month produces more intrigue about a growing investigation, rather than closure.

Just as in chapters 20 and 21, the mechanics of character introduction and plot direction don’t limit symbolic importance in the installment’s final chapter. Spatial movement plays an especially large role at the end of this installment, when Mr. Snagsby and Mr. Bucket advance towards Jo in Tom-All-Alone’s. The third-person omniscient narrator privileges the perspectives of Snagsby and Bucket in the descriptions of the neighborhood and its inhabitants. The neighborhood is described as an otherworldly, hellish landscape.

“Between his two conductors, Mr. Snagsby passes along the middle of a villainous street, undrained, unventilated, deep in black mud and corrupt water—though the roads are dry elsewhere—and reeking with such smells and sights that he, who has lived in London all his life, can scarce believe his senses. Branching from this street and its heaps of ruins are other streets and courts so infamous that Mr. Snagsby sickens in body and mind and feels as if he were going every moment deeper down into the infernal gulf.” (358)

This description of the poor neighborhood sharpens the contrast between the juxtaposed characters and setting. Most notably, Snagsby’s astonishing fear contributes to the social critique in Bleak House about willful ignorance of the affluent.

The brickmakers’ families also play an extensive role in this installment, as the women interact with Snagsby and Bucket while their husbands are drunk, unconscious, and out of work (359). One notable conversation takes place about the families’ conditions. Bucket lectures Liz about her desperate idea that her child may be better off dead than alive (360). This is important because it shows Mr. Bucket’s disconnect with the realities of life in Tom-All-Alone’s. The shelter well-off people have from the reality of poor neighborhoods, to the point that may never know it exists and will likely never understand the toils, is another example of ignorance in affluence made in the Tom-All-Alone’s scene.

Although the seventh installment may not seem significant in the initial consumption of this serial portion of the serialized whole, key events that precipitate in later installments would not be as successful without these three highly functional chapters to establish imperative characters and important physical spaces. In fact, there is compelling evidence in Dickens’s working notes that supports the idea that the seventh installment is a purposely functional issue intended to operate as a springboard to propel the coming plot. The page dedicated to this installment is the only notes page that has a list (“Mems for future”) of projected events for the section’s featured characters. This is suggestive that the genesis of the discussed characters for this installment were created as tools to achieve the completed Bleak House, and therefore it holds, that the September 1852 installment carries great functional significance.