Serial storytelling is a practice that has been popular since the 19th century and has only grown into its multidimensional medium with the development of television, books, and video games. Many early writers have been credited with beginning the art of serial novels, but none more famous than Charles Dickens. Dickens wrote dozens of serial novels; however, one of his most well-known serials is the novel Bleak House, which is split into twenty monthly parts. The central focus of this story is a never-ending court case that connects a variety of different people through various mysteries, secrets, and plots. While these mysteries carry the story and build up a very interesting and odd set of characters, they do eventually have to be solved as the story wraps up, and Dickens begins the process of wrapping up in part eighteen. There are many important, heavy moments, including Lady Dedlock’s death and Sir Leicester’s immediate decline in health. Section eighteen also serves to connect strings between unlikely characters like Jenny and Lady Dedlock. While the piece itself is often considered a standalone section that’s part of Dickens overall serial, it is more important to consider it as part of a whole novel and see how this section affects the whole piece. Section eighteen brings every character together to finish the final plot, and through Dickens’ working notes, the audience can see the focus he places on characters, pacing, and weather to create moods and themes throughout the novel.

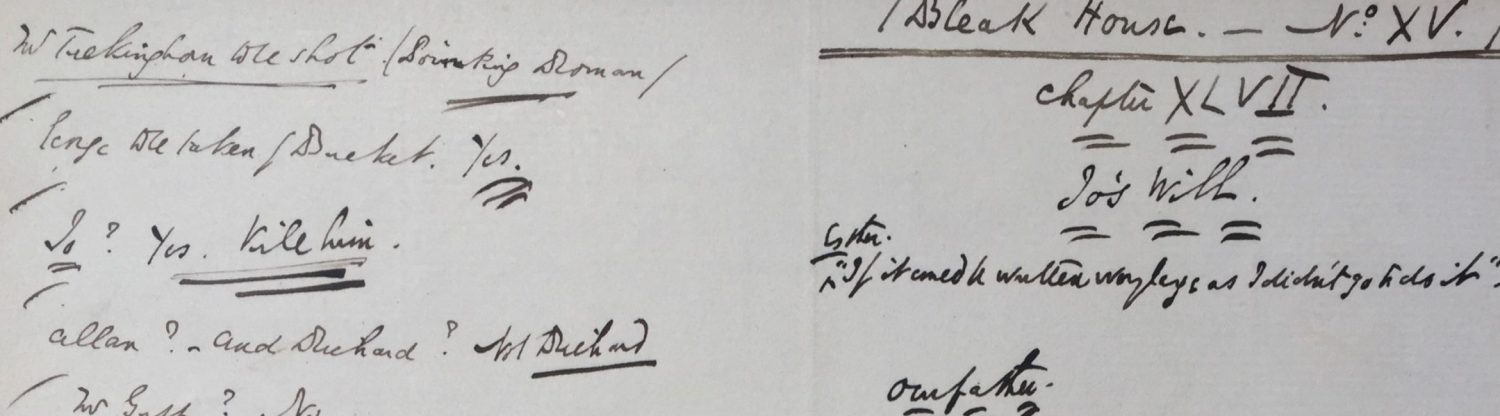

One of the defining features of Dickens’ Bleak House is how character-driven it is from beginning to end. Within the first few chapters, the audience is introduced to an array of people from the kind-hearted Esther to the mysterious Nemo to the depressed Lady Dedlock. When it comes to characters, Dickens never shortchanges his audience, and he always manages to account for every person throughout the novel. Based on his working notes for part eighteen, Dickens recognizes this abundance of characters because half of the notes are focused on said persons. With notes such as “Mr Bucket and Esther. Snagsby’s and Guster? Yes. Mr Boythorn? No…”, it’s obvious that Dickens was working through exactly how to approach the final 100 pages of his novel. He recognized that he needed to start wrapping up character arcs, and he used his notes to work through when to handle each group, and based on the roles of Esther, Mr Bucket, and the Snagsbys in this part, he has begun to do just that. This is most prominent with the Snagsbys. Throughout the story, the miscommunication experienced between husband and wife is almost comical as Mr. Snagsby works to help and understand poor Jo’s role in the investigation while Mrs. Snagsby is convinced her husband is cheating on her and has a secret lovechild. The whole plot is absolutely ridiculous, but Dickens seems to consider it an important enough point that he works to complete it. By chapter 59, it is finally resolved by Mr. Bucket who explains how, “[Mr. Snagsby] with no more knowledge of it than your great grandfather, was mixed up (by Mr. Tulkinghorn deceased, his best customer) in the same business, and no other… And yet a married woman, possessing your attractions, shuts her eyes (and sparklers too), and goes and runs her delicate-formed head against a wall.” (P. 908) In one short conversation, Dickens solves this silly side plot in one conversation with Mr. Bucket, who has taken it upon himself to fix every issue in the book. However, it’s not how the scene is handled that is important. It’s the fact that Dickens chooses to handle it at all. He could have very well just left that alone and let the audience believe that this strand of distrust lasted forevermore in their relationship. But Dickens does solve this issue, and that just goes to show how important his characters were to the greater plot of the story. Every character in the story, whether they’re a main character like Esther or a less recognized one like Mr. Boythorn, is important to the overarching plot. This story was written as a social satire, and every character plays their role. The Snagsbys stand for the obsessive nature of women meddling in the lives of their husbands, and Dickens does his best to convey this. Every part of section eighteen connects to the overall plot, and by drawing up conclusions for at least some of his dozens of characters signals that the story is coming to an end and the overall plot is finally being fully addressed and understood.

Another important facet of this novel is the use of suspense and pacing. For most of the novel, Dickens approaches the story in a very slow manner, taking the time to introduce every individual character and setting. For the first half, the readers are slowly emerged into a universe that readers in the 1800s are familiar with because it’s meant to imitate real life. He takes a long time to finally piece together the little plot points of the story from Nemo’s death to Esther’s family. However, considering this story was released in monthly parts, it seems even slower. Dickens is doing just enough to keep his readers interested, but it isn’t until the last quarter of the book that the plot really picks up, especially in part eighteen when the hunt for Lady Dedlock hits its peak. The working notes lays out everything that Dickens wants to include from “Explain it at the last” to “Guster causes delay…” to very specific details about the weather during the hunt. The notes themselves are very short and kind of frantic in the same way that the actual chapters are; however, what is most interesting is the direct contrast in his notes between the insertion of a quick chapter at Chesney Wold and the phrase “Carry on suspense” that is written at the top of that chapter’s notes from Dickens. Inserting this scene seems to be the opposite of carrying the suspense; however, on closer examination, the chapter does a lot to build tension in a more covert way. One of the lines that stands out is a line from Sir Leicester Dedlock, when he says, “‘Let it be known to them, as I make it known to you, that being of sound mind, memory, and understanding, I revoke no disposition I have made in her favor. I abridge nothing I have ever bestowed upon her. I am on unaltered terms with her…” (P. 895) This moment is a perfect example of subtle suspense because it raises the stakes on finding Lady Dedlock. Knowing that Sir Leicester is willing to take her back with no qualms if she returns to him, suddenly, this hunt is more about bringing Lady Dedlock to her senses than catching her to charge her with any actual complaints. It’s a confusing moment because the audience is left to think about whether they want her to be caught or not, and then, when they’re thrown back into the fray of the search, they want to find her just to know what will happen. Even though he cuts the tension with a little flash of a much quieter scene, the quiet only increases the suspense and the need to read on. This pacing is what makes this novel such a good serial read. Dickens reveals just the right amount of information even in his slower parts, and it’s just enough to keep the readers invested in everything that’s going on. This incredibly fast closing of the story complements the very slow beginning and middle. It makes the audience feel involved in the plot because the slowest parts feel like living any normal day, but those few quick parts are just enough to add novel value to a story all about the whims of the rich and how it affects those that aren’t rich. Dickens seems to recognize this need for a quicker pace, and he even spends time trying to figure out when and how he should include certain information. When it comes to quick reveals, he considers when to mention that Lady Dedlock and Jenny switched clothes when he writes “Explain it at the last” in his notes. He knew that discussing it too early would kill the suspense, so he waits until the very last moment, on page 915, when Mr. Bucket tells Esther they changed clothes at the cottage. It’s an important revelation, but he doesn’t stay on it for long, and instead, he moves on immediately to Lady Dedlock’s death. This novel is meant to catch the reader’s attention, and its sections like part eighteen that does just that, dragging them in right when they might be losing some sort of interest in the end. He is pacing just right by switching into full gear with hit after hit of action in these final sections.

Scenery is something else that lends itself to the pacing of this story. Dickens always takes the time to lay out exactly where his story is taking place whether it be paragraphs upon paragraph describing the fog, like he does in chapter one, or the use of exact street names. The first chapter in part eighteen is all about the scenery, and Dickens mentions actual details and quotes in his working notes that he wants included. Phrases like “Journey through the snow.” and “Thaw coming on-” are both good examples, and while the chapter is focused on action and it seems odd to note down scenery details, the scenery actually lends itself to the action here. On page 880, Esther mentions that “Although it was extremely cold, the snow was but partially frozen, and it churned — with a sound as if it were a bench of small shells — under the hoofs of the horses, into mire and water.” This little detail seems to describe the search as a whole: it’s hopeless, and they keep slipping around and missing their target, but with the melting snow (the thaw mentioned in Dickens’ notes), there is the promise of better and warmer times to come. The details tell a lot by saying a little which is something Dickens does throughout this novel. The little nods towards weather–be rain during a time of sadness or a foggy day to show mystery– allow the audience to understand the tone of different sections. While this story is meant to be a satire, it also does more than just make fun of the lives of the rich. It faces the ideas of death and longing and madness all in a very serious way, and Dickens does a good job at signaling to the reader when it’s time to laugh and when it’s time to contemplate what he’s trying to say. This section deals with humor and seriousness all in one go, and the use of weather and urgency really conveys this point and allows the audience to react properly.

While it’s impossible to ask Dickens what he was trying to say in each of his novels, his working notes do it for him, in a way. They’re a chance to see his writing and thinking processes while also offering little hints about what’s to come or where ideas connect. Bleak House’s working notes are filled with all kinds of thoughts and plans, and section eighteen in particular lays the brickwork for a beginning to the end. From direct quotes to characters, Dickens puts thought into everything when writing each section, and it’s through these notes that the audience can make the connections between individual sections and the whole novel. Serial fiction is about smaller parts creating a bigger whole, and nobody does it quite like Dickens who takes the smallest detail and makes it a motif for the entire thing, and it’s his notes that let us spot this. It’s his notes that build these connections and, ultimately, connect the book within itself.