Perspectively Questioning Bleak House

ENG491H Spring 2020 – Installment IX

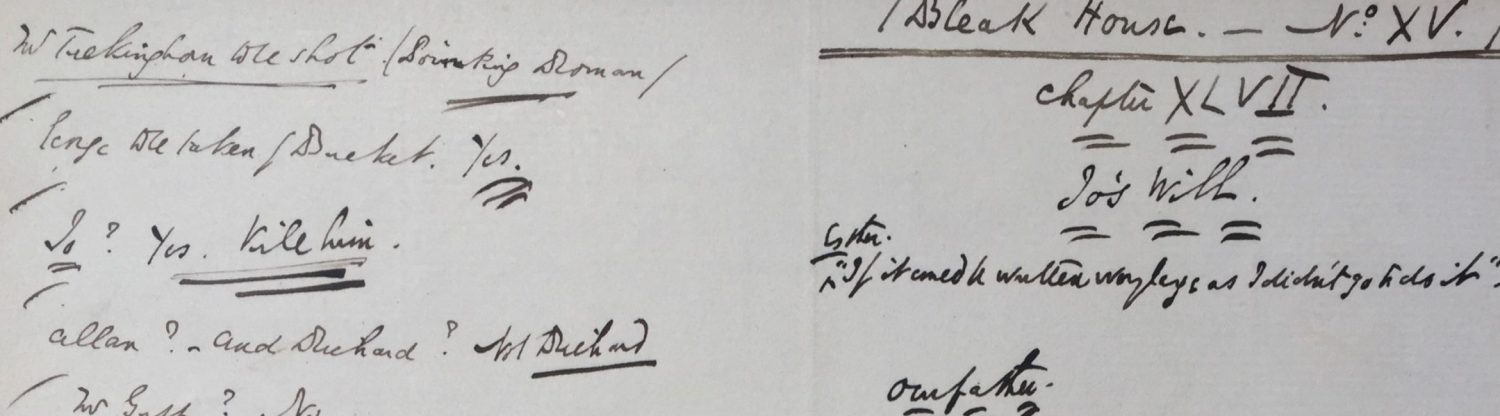

In the working notes of Dickens for Bleak House, he uses question marks to note that he hasn’t decided whether to include characters yet or not. However, for the number that I worked with – number nine – he did this for all but one set of the characters he considered. This made me think more thoroughly about how he does this process and consider what goes into it. For some characters, he did include them, while with others he just included characters that would reference them instead. Otherwise, he didn’t include them at all. This plays strongly into the way he manipulates the reader’s point of view by obscuring their ability to see the whole picture – they only get a limited viewpoint into the whole story, unlike his omniscient point of view he uses in contrast to the other characters like Esther. The characters he does introduce, however, are essential for that number.

For this installment, Dickens uses the Smallweeds to introduce who the unknown character is and provide a link between Esther and the unknown character. He also spends time with Tulkinghorn, who is connected to Hortense – a character who was considered for this number but wasn’t directly included. Mr. Guppy starts to connect Lady Dedlock to Esther as well, which twists the readers’ perspective as they come to grips with why they look so similar.

The ways that connections are used in the introductions and interactions are essential to a work like Bleak House. Additionally, another character questioned, Hortense wasn’t mentioned or added, but the connected character, Tulkinghorn, was discussed for two chapters of the number I worked with. The relationship is still built up without the “French woman”, and she can be introduced much later in the serial work than he first considered. However, even through characters that weren’t brought up in the ninth release of Bleak House, the working notes are inherent reminders of connections between them – Dickens never separates connected characters from each other when he makes his lists of connected characters, only listing characters right after each other or together because they are related to each other.

This helps give insight on what the thought process for the working notes followed: it may have been assumed to “jog memory”, but it also helped keep down all the connections between the characters that Dickens could forget to include if he didn’t write it down. I also noticed an aspect that told me the order of which the working notes was written – the left side is filled out first, and then the right side is filled in with details. I noticed this because of his note of including “Mrs. Rouncewell’s other son, or Watt, or Rosa”. On the right side of the page where he organises where he will talk about it between the chapters, he changes the phrasing to “and” instead of “or” – he has decided to include them all, not choose between them. This helps with understanding the use of question marks – rather than idly not caring, it gives more leeway for certain ways of things being described and how to go about showing the event.

He has a certain way things fold out in the novel, but some things don’t have to be told in an exact order. Since there is more freedom to work with the characters in a way that flows more openly, Dickens uses that freedom to manipulate his readers’ understanding. Particularly, he uses the omniscient narrator to tell this whole number – a choice that prevents connection with a particular character that may make certain details difficult to contain. This choice, along with the characters he included and focused on for the whole number, were due to the place in the novel he had gotten to. The exact timing of details being told weren’t quite essential, yet he had to make those decisions precisely, and make them in a way that brought out the connections best.

There is a deep level of care put into how characters are introduced, interacted with, and manipulated in the reader’s point of view. As I noted in the previous paragraph, Dickens mainly makes notes of the connections, though he leaves tips for himself about how those connections occur if they are complex – such as Lady Dedlock finding that Esther is her child. It’s possible to jump into the way that he may have viewed his writing process – a full story already present, with the choice of perspective all his. If he had chosen to write from another perspective than the omniscient narrator, surely he would have chosen Lady Dedlock – this would alter the course of that chapter, and perhaps provide spoilers to the end of the chapter rather than postponing it to the end, which was the end of the whole release to be published for that number.

This installment working notes gave a lot to work with abstractly – mostly on Dickens’ way of using the notes. The notes had the headers written in first for sure, but the notes themselves were first for characters on the left page and more specific notes on the right page as he presumably wrote Bleak House and did other things. The character notes were most intriguing to me, as they provided the most insight to this process in my installment. They were the focus of the installment, as character connections were made, and details of characters were fleshed out as well. In the way it was presented, it still maintained a sense of the unknown perspective that was necessary to carry through the whole novel.