In Bleak House, Charles Dickens has created an exponential number of characters whom he has formed out of varying shades of greed, deceit, and selfishness, all in the name of satire. The few characters that he has chosen to embody those characteristics that do not incite excitement in his serial novel – kindness and sense of duty – he leaves to fully flesh out until the end of the narrative, maximizing long-term investment for the reader. The two characters who embody these characteristics are George and Esther. George, a reformed man of duty, is held in contrast to those others who manipulate individuals like Jo in order to give the reader a reprieve, endearing him to readers in a passive manner. Esther, adored by all who know her for her simplicity of moral character, is the reader’s conduit into this world of deceit and lies and actively cheered for by readers for this reason. This final installment gives readers two drastically different conclusions of caretaker-ship for each of these highlighted characters. George ends as the son that he was always made out to be, taking his mother to church and helping maintain a quality of life for his pseudo-father, Sir Leicester. Esther is rewarded with the perfect picture of domestic bliss at the time: to be a country doctor’s wife with two daughters of her own and a surrogate son through Ada. Although this novel is known for its mistreatment of characters at its own hands, Dickens’ utilizes these two characters to provide a sense of relief for the tension that he deftly creates throughout.

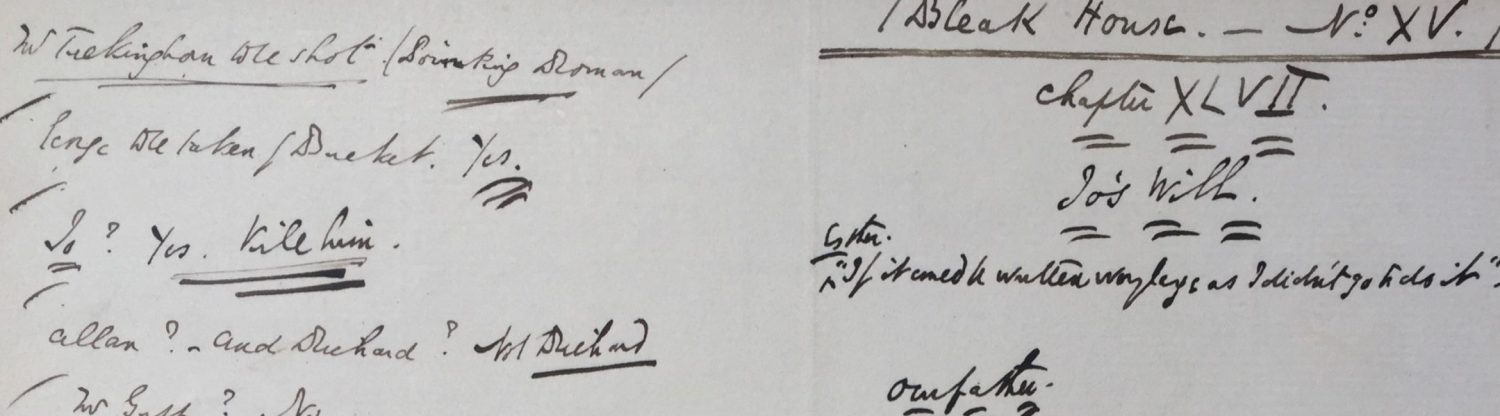

Charles Dickens’ final two installments of Bleak House were published together in September of 1853. As compared to the publication of the other installments – one per month for seventeen months – these final two are published simultaneously in a carefully planned ending to a long, painstaking narrative. Rather than splitting up the components of this orchestrated ending, Dickens chose to utilize this double publication to expand his final timelines. In these final installments, Dickens lays down the framework for the conclusion of each of his main characters through a mixture of future-Esther looking back, present-Esther, and the omniscient narrator looking in on the goings on of multiple characters. He lays the groundwork of Richard’s impending death through a glimpse at the final moments of true domesticity for the novel’s “it couple.” He wraps up the storyline of smaller characters through a final interaction with Skimpole, showing Mr. Guppy making a final proposal, and allowing Nemo to be mentioned a final time in a letter from George to Esther. He also finalizes plotlines woven carefully throughout showing readers the confession of love by Allan Woodcourt and the acceptance of marriage to Jarndyce by Esther, concluding with Esther’s placement in a new Bleak House with Allan Woodcourt as her husband. Finally, to conclude any points of contention throughout the narrative, Dickens kills off Richard following the conclusion of Jarndyce and Jarndyce stemming from a will produced in the last few pages of the book. He manages to bring each of his characters full circle, despite the staggering number of them.

From his very introduction, George is defined by his kind, long ranger attitude. He does not marry, even when circumstances have presented themselves to him in the past, and he ingratiates himself in relationships in which he can be benefactor but not receiver. His sole mission in this world is to be kind to others in the best way he knows how, much like Esther. He does allow for some characters to take care of him throughout the novel, such as the Bagnets with Mrs. Bagnet being the key player, but he seems determined to pay penance for a crime that others cannot identify, keeping him from accepting love. It is not until the final chapters of this narrative that readers learn his true sin is that he chose to be away from his family for many years, leaving them to wonder whether he was dead or alive. While the rest of his character speaks to an unselfish heart, this hangup keeps readers from always reading him as a pure intentioned character; however, he states “But I should not have been surprised, brother, if you had considered it anything but welcome news to hear of me” (954). He is not a man looking for deliverance, but a man seeking reformation in any way that he can from the sins he has committed, eventually accepting love through acts of service.

He epitomizes this ideal by taking care of a variety of individuals throughout the novel, culminating with his taking on Sir Leicester in what are implied to be the stately man’s final years. Throughout the novel, Dickens shows readers George’s capacity for love and kindness through his interactions with individuals that are persecuted by others or being searched after by Mr. Bucket. His strong sense of moral right and wrong allows him to not be sent down the tumbling staircase of greed and anger that seems to consume most other characters, and instead to constantly be in review of his own qualities. He tells his brother upon meeting him again that, “I am a kind of a Weed, and it’s too late to plant me in a regular garden,” indicating that he feels his place in society is to be moved from one area of nourishment to another in order to showcase the beauty of other things and not himself (956). Despite his self-deprecation, he inspires loyalty to his identity beyond his status in the world: his mother accepts him back with open arms, his brother bolsters his sense of self in just one meeting, and the man who was so fond of him as a child decides to bring him into the fold in order to better manage his own quality of life. George as a caretaker is key to the conclusion of Sir Leicester’s story as it gives him a purpose beyond taking over his brother’s business that he could very easily have usurped and a father figure to make proud. Sir Leicester has a piece of his past that is not tainted by the death and scandal of Lady Dedlock by having George in his life. This keeps the whole scandal from eclipsing his storyline and allows him to end life in a place of relative comfort, which is the least Charles Dickens owes to Sir Leicester. George is a force of renewal for all that he comes into contact with.

A force of stability and a touchstone for many characters, Esther repeatedly works as a gentle source of love from the outset. Although she comes from a place of deceit and betrayal, she epitomizes the potential in every child for unconditional love of others, even when seeing oneself as unacceptable as a result of past traumas. In the course of the novel, the change in her appearance following an illness she contracts after helping Jo and Charley is shown as the hardest personal tribulation she faces solely on her own. Subliminally allowing herself to be punished for her kindness, much like George with his short imprisonment, she is forever changed by the intense situation and repeatedly doubts that anyone can value her the same. She believes her mere existence is a crime that she must be paying penance for. Following this, she loses her sense of self with this illness and tries to be what she thinks others want her to be by accepting John Jarndyce’s marriage proposal following her recovery. She believes herself to be this “little woman” that she is frequently labeled as. In line with her consistent submissiveness, she allows herself to slip into her final role of domesticity when Jarndyce gives her a home for her and Allan Woodcourt without much, if any, questioning. She allows others to hold the self-confidence for her and follows along willingly when John Jarndyce presents the house to her “knowing there could be no better plan, [he] borrowed [hers]” (962). As the readers have a blueprint for who they believe Esther to be, Dickens is able to capitalize on this with Allan’s lack of characterization in terms other than a selfless doctor so he can place this woman with seemingly few, if any, negative qualities perfectly with him. She is rewarded with an unproblematic man and able to have someone else hold her sense of self for her in a way that is actually beneficial to her wellbeing. Her kindness and passive existence have been cherished and deemed worthy of completing in the kindest sense of the era by Dickens.

In the final two installments, Dickens shows that despite being willing to punish greed and duplicity with death and loneliness, simple goodness will be rewarded with simple acts of kindness and partnership in the forms of George and Esther. George as a caretaker is pivotal to the conclusion of Sir Leicester’s story and allows George to find fulfillment in taking care of a man torn to shreds by his own misunderstanding of his world. Esther is finally given something of her own, solidifying her character as one of true substance and not just a fly on the wall of all of these scandalous occurrences. Dickens shows readers in the final notes of his manuscript that there will be sadness and punishments for those who did not care for others in a selfless way, but that he will care for those who seem to hold little substance due to their morally upstanding character. Despite it being a satire of the world at the time, Dickens still chooses to leave the reader with a bit of hope for those in this world who dream to be kind.