Installment 15 covers chapters 47, 48, and 49. Chapter 47 begins on Allan Woodcourt settling an ailing Jo at Mr. George’s establishment. Jo is made comfortable and visited by several of his friends, including Esther and Mr. Snagsby. Jo subsequently dies. Chapter 48 returns to the Dedlock family at Chesney Wold. Lady Dedlock summons Rosa and dismisses her from service with the intention of allowing her to join the Rouncewell family in marriage to the son of Mr. Rouncewell. Lady Dedlock conferences with Rouncewell and Sir Dedlock in the presence of Mr. Tulkinghorn, and she releases a sorrowful Rosa into Rouncewell’s care. Later, Mr. Tulkinghorn confronts Lady Dedlock, who he accuses of reneging on their agreement to remain as normal until Tulkinghorn decides on how to proceed with Lady Dedlock’s ordeal. He also accuses her of attempting to protect Rosa from her scandal. He announces the agreement void and declares he will proceed on his own terms with conveying the matter to Sir Dedlock at his leisure. Mr. Tulkinghorn returns home. A gunshot is heard. The chapter closes on an explosive discovery—Mr. Tulkinghorn is found shot dead in his chambers. Chapter 49 focuses on the Bagnet household, where Mrs. Bagnet is celebrating her birthday. The other Bagnet members perform her usual household duties, often to her quiet dissatisfaction. A low-spirited Mr. George and Mr. Bucket attend the festivities, where Mr. Bucket charms his way into the family’s affections and next year’s celebration. Mr. George departs and Mr. Bucket accompanies him; Bucket then informs George of Tulkinghorn’s murder and his knowledge of George’s presence at the scene of the crime. The installment finishes on George’s arrest.

As I will argue in this paper, Dickens uses London as a means to critique the urban spatial paradigm—the overpopulation, pollution and poor sanitation, lack of welfare support systems, and the inefficacy of the justice system that does more harm than good. I suggest that the fifteenth installment of Bleak House exemplifies the issues Dickens raises. The deaths of Jo and Mr. Tulkinghorn and the arrest of Mr. George ultimately signal the corruptive force of the urban landscape that Dickens reiterates throughout the novel. In support of my interpretation, I analyze specific moments from the fifteenth installment, as well as the novel as a whole. I ultimately contend that Dickens’ social critique underlies a deeper dissatisfaction with the societal moral decay that the city represents.

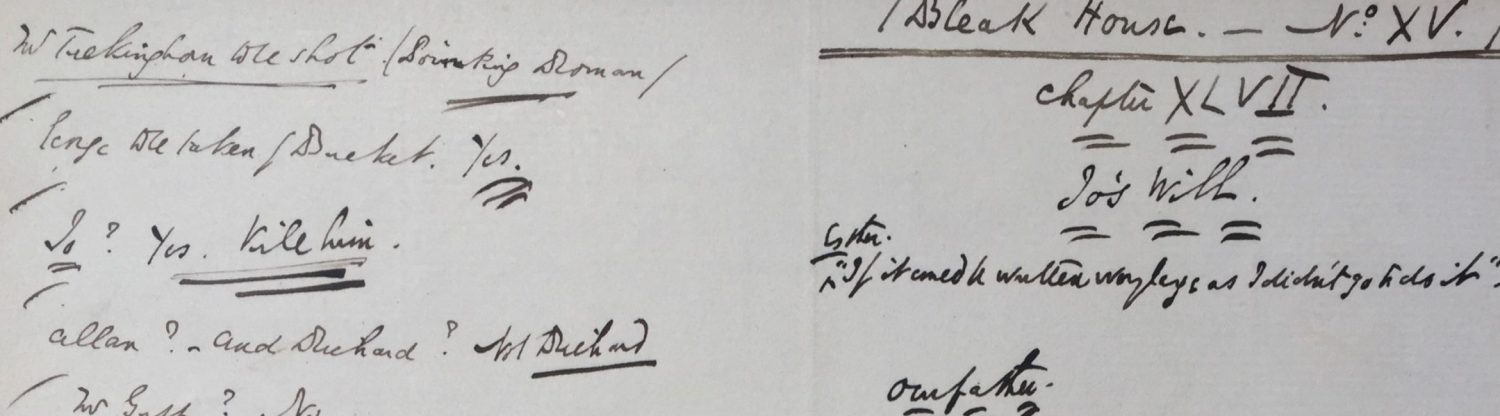

Jo’s Will

In chapter 47, Dickens highlights the limits of urban philanthropy. With poor (or nonexistent) welfare support systems, characters such as Jo, Jenny, and her ilk live in the squalor of Tom-All-Alone’s. The most that can be done for Jo is a few coins now and then from Mr. Snagsby and the comfortable deathbed experience provided by Mr. Woodcourt, Mr. George, and Phil. When Esther previously attempted to assist Jo, he was made to move on once again by Mr. Bucket: the model urbanite, the one who represents all the failings of the city—the crime, the injustice, the antagonism of the poor (as seen with Jo). The best services done for Jo already after he has already been made a victim of the city, only once he is death-bound may he be helped without hindrance. He is given food, clothing, and shelter after it is all but certain that he will nevermore have a chance for rehabilitation, for a future in English society. At one point, Dickens writes:

He is not one of Mrs. Pardiggle’s Tockahoopo Indians; he is not one of Mrs. Jellyby’s lambs, being wholly unconnected with Borrioboola-Gha; he is not softened by distance and unfamiliarity; he is not a genuine foreign-grown savage; he is the ordinary home-made article. Dirty, ugly, disagreeable to all the senses, in body a common creature of the common streets, only in soul a heathen. Homely filth begrimes him, homely parasites devour him, homely sores are in him, homely rags are on him: native ignorance, the growth of English soil and climate, sinks his immoral nature lower than the beasts that perish. (724)

In invoking the image of Amerindian and African peoples, Dickens challenges prejudiced notions of the incivility and savagery of the nonwhite masses and what later comes to be known as the doctrine of White Man’s Burden (1899). Simultaneously, he also denies that Jo’s state may be attributed to foreignness. Jo is English. As Dickens implies with his critiques of Mrs. Jellyby, one does not have to cast their net far or abroad to find social, cultural, or moral deprivation; these are issues one may find at home, domestically. Jo’s dereliction is a failure of English society, a failure to provide for and protect its own English progeny. Without family, without home, without moral guidance and education, what separates those on the lowest rungs of English society from the brutes internationally?

Closing In

Dickens’ word choice subtly privileges the countryside over the city. Even when attempting to grant positive attributes to the city, Dickens underscores the drawbacks of the city–the pollution, the noisiness, the overpopulation. In the paragraph preceding the infamous line about the shot that rings out in the night, ultimately signaling Mr. Tulkinghorn’s death, Dickens dilates the narrative’s spatial shutter to encompass England as a whole. He details the various areas across the country. In his description, he attributes more positive descriptors to rural areas and more negative ones to urban and industrial areas. Quiet in pastoral areas is where, “the water-meadows are fresh and green, and the stream sparkles on among pleasant islands, murmuring weirs, and whispering rushes,” (749; emphasis added). This constrasts with industrial cities and mill towns where, “houses cluster thick, where many bridges are reflected in it, where wharves and shipping make it black and awful, where it winds from these disfigurements through marshes whose grim beacons stand like skeletons washed ashore,” (749; emphasis added). Similarly described, the London metropolis is, “this stranger’s wilderness,” where, “its steeples and towers, and its one great dome, grow more ethereal; its smoky house-tops lose their grossness, in the pale effulgence; the noises that arise from the streets are fewer and are softened, and the footsteps on the pavements pass more tranquilly away,” (749; emphasis added).

Dutiful Friendship

The final chapter of the fifteenth installment, chapter 49, initially focuses on the domestic felicity of the Bagnet household, an aberration in the urban spatial model. Near the end of the chapter, Mr. George is arrested for the murder of Mr. Tulkinghorn, which given reader knowledge of Tulkinghorn’s relationship with Lady Dedlock, his imprisonment may generally be considered erroneous. As later chapters reveal, George’s imprisonment disturbs the tranquility of the Bagnet household, who believe their close friend to be innocent. When considering the novel as a whole, the Bagnet family is one of the more successful examples of the traditional, nuclear family in the novel. And why is that? Couples where the wife is assertive or leaves the domestic sphere for the public sphere, and/or where the husband does not take on the provider role often results in unhappy marriages or familial life. Consider the Skimpoles, the Snagsbys, the Jellybys, the Turveydrops, and the Pardiggles. The Skimpole household is in disrepair and financial ruin as Mr. Skimpole is unable to take on the provider role. The Snagsby household is plagued by unhappiness as Mrs. Snagsby angsts about Mr. Snagsby’s possible infidelity and neglect of Jo, who she presumes to be his child. The Jellyby household is also in disrepair with neglected children and a depressed husband as a result of Mrs. Jellyby’s prioritization of her international philanthropic efforts. Old Mr. Turveydrop’s wife, the provider of the family, dies and her burden is left to Prince Turveydrop to ensure his father’s maintenance. Even though Caddy and Prince are likely better off in their familial future, their baby bears the marks of her parent’s suffering at the hands of their parents. With the Pardiggles, the unhappy children resent their mother’s forays into public philanthropy. By contrast, the Bagnets enjoy domestic bliss as Mr. Bagnet works and provides for the family while Mrs. Bagnet ensures the maintenance and happiness of the household. All of the aforementioned families live in London, so what is it about the city that breeds such high rates of familial discontent? Perhaps for Dickens, the urban life affords more opportunities for women to break from their traditional roles, but instead of celebrating this phenomenon, Dickens critiques it.

Bleak House, as a whole

As I have argued, the fifteenth installment exemplifies the critiques of the urban spatial paradigm that Dickens inserts throughout the novel, while also demonstrating his affinity for traditional country living. These sentiments may also be seen when you consider the conclusion of the novel and the novel as a whole. Esther, Ada, and their respective families find their happiness in Bleak House, situated in the country. Mr. Jarndyce often expresses a preference for staying in his personal Bleak House, away from the city and its Court of Chancery. Lady Dedlock, who early in the novel often flits between London and Lincolnshire at her leisure, goes on her ill-fated journey through the countryside before meeting her final demise in the city. Consider that all of the major character deaths in the novel occur in the city—the late Mr. Jarndyce’s suicide in the coffee shop, as well as the deaths of Captain Hawdon and Mr. Krook at Krook’s Court, Mr. Gridley and Jo at George’s shooting gallery, Lady Dedlock at the poor cemetery where Captain Hawdon is buried, and Mr. Tulkinghorn at his offices/rooms, all in London.