The fourth installment of Charles Dicken’s novel Bleak House was published in June of 1852, and the installment in question is more significant than an initial reader may have thought. Containing chapters eleven through thirteen, the number chronicles the aftermath of the death of a law writer, Captain James Hawdon, who called himself Nemo, and his eventual burial. Nemo’s body has been found by Tulkinghorn, who also discovers that the boy Jo, a character that will later become of more significance, is connected to him. It also features the return of Sir Leichester and Lady Dedlock back at their home Chesney Wold, who receive the news on Nemo, who wrote a paper that distressed Lady Dedlock in the early chapters of the novel, from Tulkinghorn. Meanwhile Esther finds herself avoiding Mr. Guppy while Ada and Richard announce their future intentions for marriage. While beginning the main mystery of Nemo and his identity, this number reveals a great deal of information about who Esther’s parents are or were as people, and, especially through their interactions with children and young people, Dickens hints at Esther’s heritage. It also chronicles an overall theme of avoidance that the novel has, a trait shown by multiple characters throughout this installment, an inclination that creates a familial thread tying the novel together.

While the initial reader most likely would not have been aware that Nemo and Lady Dedlock, two figures at complete opposites of the social ladder, would in fact turn out to be Esther Summerson’s parents, they both share a few similarities in this number. Esther in earlier parts and in this installment, is a protagonist that exudes kindness not just to her close friends like Ada and Richard but in multiple instances children as well. A notable moment is her friendship with Mrs. Jellyby’s neglected son Peepy, and a more somber one occurs with Jenny’s dead infant. Both parents, though not known to either Esther or the reader at the time, show kindness to child or younger characters in their respective chapters of focus. Lady Dedlock asks the new maid Rosa: “Why, do you know how pretty you are?” (185). Meanwhile, Jo, reflecting on his interactions with Hawdon, says “he wus wery good to me, he wus!” (181).

This section then serves to help define who Esther is both thanks to her heritage, her parents, and her friends. This number also continues the theme of Esther’s avoidance, and demonstrates how her parents share this trait as well. Hawdon is generally characterized as avoiding people apart from Jo, and because of this avoidance further investigation into his death is not formally pursued. Meanwhile Lady Dedlock avoids Tulkinghorn’s pursuit of her, attempting to keep her secrets from him. Finally, Esther’s avoids introducing Allan Woodcourt at all, a major character in the later numbers of the novel who is almost completely “omitted” as Esther puts it, in his first appearance. She only writes on him after the first meeting has occurred, and seemingly only because Ada asked her about him. She writes: “he was rather reserved, but I thought him very sensible and agreeable. At least, Ada asked me if I did not, and I said yes” (214). While spending her narration chronicling in detail the romance of Ada and Richard, Esther desperately attempts to avoid any topic of her own romantic or even sometimes just friendship based relationships. With this introduction of Allan Woodcourt, Dickens begins developing one relationship that will last while continuing one that will not with that unfortunate pairing of Ada and Richard.

Avoidance follows all three members of this family, even if the reader is unaware of this familial thread, there is a thread of connection in how all hide something, whether it be secrets, writings, or romantic interests. Esther is a resistant narrator, and she seems to socially exclude herself both in the narrative herself and in the structure of the novel. Esther, being the primary narrator, is a unique one because of her constant attempts to minimize her role in the story and herself as a character. Even in her initial chapter in the first installment she ends her narration by assuring the reader that: “my little body will soon fall into the background” (40). In this installment, Esther demonstrates this avoidance by trying to hide from Mr. Guppy, who has proposed to her in a previous chapter. While in London, Guppy pursues her at the theater and outside of her bedroom window, a situation that causes Esther be “afraid to go near the window when I was upstairs…lest I should see him” (204). Esther avoids the window of her room and also avoids filling her “windows” of narration, her chapters, with herself.

Esther’s parents are resistant narrators in this installment as well, all three of these characters seemingly conceal their identities, whether unintentionally or intentionally. Lady Dedlock and Hawdon’s attempts are taken to the extreme, with both having completely disconnected themselves from their past lives, Nemo literally meaning “no one” in Latin as noted by Tulkinghorn, while Esther performs this act of concealment through her own narration. Lady Dedlock, like Esther, appears to keep her true self hidden, despite being praised by both the omniscient narrator and those around her like the servant girl Rosa as “so graceful, so beautiful, so elegant” this installment features more of Lady Dedlock’s true feelings (186). One instance of her performing this avoidance is how Lady Dedlock, in her pursuit of information on the death of Nemo, feigns interest in “horrors” when pursuing answers about the man she once knew as Captain Hawdon, calling Nemo “wretched” and “deplorable” in her questions to Tulkinghorn to avoid further suspicion (195). Dickens foreshadows future character development, stating “weariness of soul lies before her, as it lies behind” (182). Dickens also establishes in this installment her distrust of Tulkinghorn: “what each would give to know how much the other knows- all this is hidden, for the time, in their own hearts” (196).

Meanwhile as far as her father is concerned, Mr. Tulkinghorn’s comment that “no one knew his name” when prompted by Lady Dedlock on Hawdon’s death, reflects the fact that his daughter’s name is also frequently hidden or obscured, like Captain Hawdon’s was (195). From early on in her living in Bleak House, Esther is called something she is not, being called “so many names of that sort that my own name soon became quite lost among them” (121). Hawdon as Nemo resists being known by anyone but Jo, and when questioned by Tulkinghorn about his tenant, Krook states: “than that he was my lodger for a year and a half and lived—or didn’t live—by law-writing, I know no more of him” (168). Even the one witness to the coroner’s inquest of Nemo’s death, Jo, is resistant, and his testimony is not accepted.

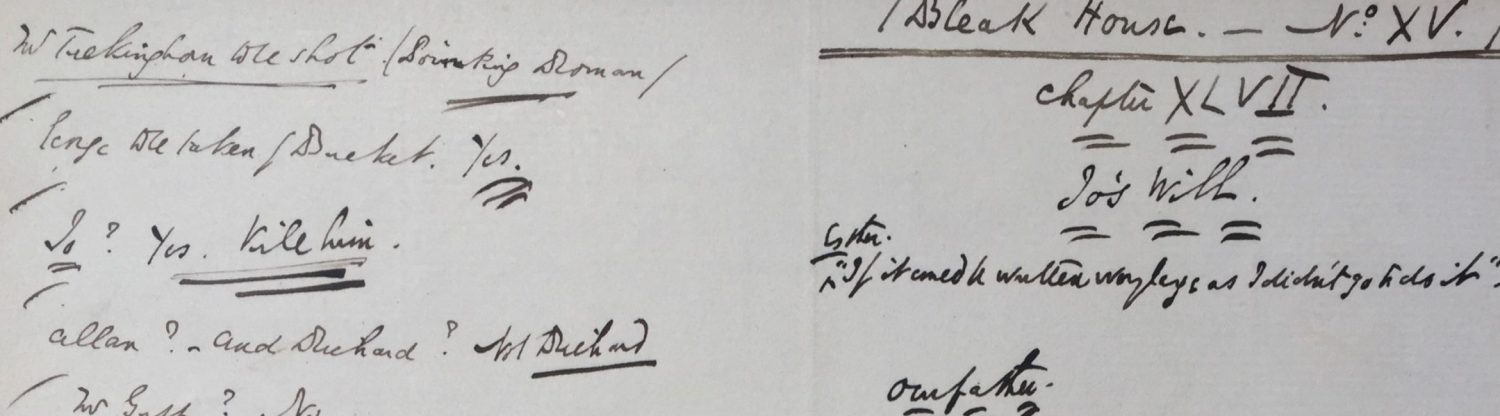

However, despite all these characters inclinations to solitude and avoidance, this installment especially demonstrates how it is their relationships and connections that bring out the best in them and will ultimately drive the plot forward. There are many moments throughout the novel where these characters’ true selves are unmistakable despite their attempts to hide themselves, and these scenes illustrate how despite their attempts at solitude, they have impacted the lives of others in a way that they can’t be completely invisible. Esther, despite her best efforts to exist on the margins of the narrative, is beloved by the occupants of Bleak House, as stated by Mr. Jarndyce in the conclusion of the installment: “some may find out, what Esther never will- that the little woman is to be held in remembrance above all other people” (214). Lady Dedlock’s kindness and interest in Rosa which is first introduced in this installment will ultimately culminate in her making a massive sacrifice to ensure Rosa’s happiness. Hawdon’s kindness to Jo meanwhile is one that is only mentioned yet still just as significant. Dickens in his notes seemed heavily interested in the final image of chapter 11, where Jo sweeps Hawdon’s grave. Dickens, in his chapter on the death and aftermath of Hawdon, uses the final scene to emphasize Jo’s line of Hawdon’s goodness to him by having it repeat as Jo sweeps around his grave, as the omniscient narrator notes: “thou art not quite in outer darkness…there is something like a distant ray of light in thy muttered reason for this.” (181).

This installment shows that by engaging in these acts of avoidance, the characters, especially Lady Dedlock, Hawdon and Esther drive the plot forward and therefore make this installment a significant one in terms of the overall novel.Lady Dedlock, after gaining her knowledge from Tulkinghorn in this installment, will later visit the grave, inciting the investigation with Bucket. Tulkinghorn’s investigation of who Nemo was and how he was connected to Lady Dedlock continues through the novel and ultimately leads to the climax of Lady Dedlock’s demise, and Ada and Richard’s relationship will be another conflict that continues up until the very last chapters. Meanwhile the character Esther makes a very strong attempt to avoid altogether, Allan Woodcourt, will end up becoming her partner. Even before anything is revealed officially in the novel, Charles Dickens connects the family through their desperate attempts at avoidance and their unavoidable kindness.